Why You Cannot Be a True Ballet Artist Without Ballet Technique

Key Takeaways:

– Ballet technique frees your mind to focus on emotion, not mechanics.

– Proper turnout and placement builds unshakeable stability.

– Controlled flexibility relies on strength, not extreme stretching.

– One precisely executed movement teaches more than many careless repetitions.

– True artistry blooms only when technique becomes second nature.

I wanted to paint a dynamic, very expressive picture of a ballet dancer in white tutu, dancing with emotions. In my head I had a perfect vision of how it would look: brown-ish background, arms up, dynamic pose, confident strokes of brush – something that would not only allow me to materialise my vision, but also show my technical skills, my mature eye, my sense of colour, my artistry

There was only one problem. I can’t paint.

The Essential Connection: Why You Cannot Be a True Ballet Artist Without Ballet Technique

Ballet is often misunderstood. Many dancers believe they must choose between being technically precise or emotionally expressive – as if these qualities exist in opposition. This fundamental misconception has led countless dancers down a frustrating path, wondering why their artistic expression feels limited despite their sincere and passionate efforts.

Many dancers worry that by focusing on ballet technique, they lose their “natural” artistry and become robotic or stiff. But is this really true?

The truth is far more liberating: you can only achieve full artistic expression in ballet when your technique is flawless. Much like a painter must first master brush control before creating a masterpiece, a ballet dancer must develop complete technical mastery to truly express themselves without limitations.

The Foundation of Artistic Freedom

What many dancers fail to understand is that technique isn’t a set of arbitrary rules designed to restrict creativity. Rather, it’s a sophisticated system developed over centuries to allow the human body to move in ways that defy our natural limitations.

Technique is not just steps or vocabulary. It’s the way you align your body, use your muscles, coordinate your movement, and control your placement. Ballet technique, in every form – barre, center, pointe, pas de deux, and the grand stage – functions as your language.

This relationship between technique and artistry isn’t casual – it’s causal. The quality of artistic output is directly proportional to the quality of technical foundation supporting it.

The Intuitive Artist: Beyond Conscious Technique

Many students and even professionals feel like technique “gets in the way” of expression. But the real restriction happens without technique. Without the right training, your body only does what feels natural (which, surprise, is not ballet). Instead of feeling free to explore choreography and emotion, your options shrink to what your untrained body can “get away with.”

On the other hand, the best professional ballet dancers perform intuitively. When you watch a truly accomplished dancer, they’re not consciously calculating each movement. Their technique has become so internalized that they’re free to focus entirely on expression.

Think of a concert pianist during a performance. They’re not consciously thinking about which keys to press or finger positions. Their technical mastery allows them to transcend mechanics and focus purely on musical interpretation. Ballet works the same way.

A professional dancer must perform intuitively because dancing at a high level while consciously focusing on technique creates an impossibility: you cannot simultaneously monitor technique and express genuine emotion.

Why Turnout and Placement Form the Core of Ballet Technique

At the heart of proper technique lie two fundamental concepts: turnout and placement. These elements aren’t merely stylistic choices or personal preferences – they’re the engineering solutions that make ballet’s unique quality of movement possible.

Turnout: The Foundation of All Ballet Movement

Turnout – the external rotation of the legs from the hip joints – creates a physical paradigm shift in how the body moves through space. Unlike sports or other dance forms that work with the body’s natural parallel structure, ballet transforms this limitation through turnout.

This rotation isn’t just about aesthetics. It provides stability, balance, and the ability to move in ways that would be impossible in a parallel position. It enables the dancer to shift weight and change directions with an efficiency that creates ballet’s characteristic flowing movement quality.

Placement: The System for Whole-Body Coordination

Placement refers to the precise alignment and coordination of the entire body. It’s not merely “good posture” but a sophisticated system for connecting different parts of your body into one, connected muscle, and about distributing weight and energy efficiently.

When a dancer achieves proper placement, their movements gain a quality that transcends the ordinary. Their transitions become seamless, creating the illusion of continuous, uninterrupted motion even through moments of stillness.

A properly placed dancer appears to move with effortless grace – not because the movements require no effort, but because the effort is distributed optimally throughout the body.

The Technique-Artistry Connection in Performance

The connection between technique and artistry becomes most apparent during performance. There are only two states for a dancer on stage: stable or unstable. And artistry can only emerge from stability.

When dancers are unstable due to inadequate technique, they experience anxiety. Their mind focuses entirely on not falling, leaving no mental space for artistic expression. The audience feels this anxiety rather than the intended emotion of the performance.

In contrast, when dancers possess rock-solid technique, they achieve a state of stability that liberates their mind. They can respond spontaneously to the music, their partners, and the energy of the audience.

This is why we see such a strong difference between dancers with genuine technical mastery and those who merely look the part. The truly masterful dancer appears to be constantly in motion, even when still, because their stability creates a continuous flow of energy.

Choreographers and the Limits of Untrained Bodies

Choreographers don’t dream up breathtaking swan arms, endless balances on pointe, or sweeping pas de deux because dancers are “naturally” able to do them. They expect – and need – dancers with technical mastery, able to execute difficult steps and combinations safely, repeatedly, and with little thought.

If, however, technique is shaky, the dancer and choreographer have to work around the limits of the body. The choreography becomes simple, and the art form – restricted. In other words, the dance is defined by what you cannot do, not what you could express!

| Without Strong Technique | With Strong Technique |

|---|---|

| Limited movements | Unlimited choreographic options |

| Prone to mistakes / injury | Reliable, consistent performances |

| Focused on “survival” on stage | Focused on expression & emotion |

| Choreography simplified | Choreography as intended by the creator |

Common Misconceptions About Ballet Technique

Many dancers fall victim to misconceptions that ultimately limit their artistic potential:

Flexibility Over Strength

Many believe extreme flexibility is the hallmark of a great ballet dancer. In reality, technique in ballet is primarily about strength development, not flexibility. While appropriate flexibility is necessary, hypermobility without corresponding strength actually impedes technique and increases injury risk.

The most accomplished dancers develop, what pedagogues call “controlled flexibility” – the ability to move through full ranges of motion with complete control.

Aesthetic Over Engineering

Some focus entirely on how ballet looks rather than how it works. They attempt to copy the visual appearance of accomplished dancers without understanding the mechanical principles that create those aesthetics.

This approach leads to imitation rather than mastery. True technique comes from understanding and applying the physical principles that make ballet possible, not from mimicking positions.

Repetition Over Precision

Many believe more repetition automatically leads to improvement. In reality, one precisely executed movement is worth more than dozens of imprecise attempts. Each imprecise repetition reinforces poor patterns and wastes the body’s resources.

One tendu done with proper placement and turnout is worth more than 20 poorly executed tendus without understanding.

Why Some (Most) Dancers Never Achieve Artistic Freedom

Despite years of training, many dancers struggle to achieve true artistic expression. This generally stems from fundamental gaps in technical development:

- Insufficient emphasis on turnout and placement: When foundational elements are glossed over in favor of advanced steps, dancers build on unstable ground.

- Focus on tricks over transitions: Many dancers excel at isolated moments of brilliance but struggle with the transitions between them. Yet it’s precisely these transitions that create the continuous, flowing quality that distinguishes great ballet.

- Misunderstanding stability: Stability in ballet doesn’t mean rigidity. It means maintaining precise alignment and turnout while in motion. Without this dynamic stability, artistic expression becomes impossible.

These limitations, for the most part, aren’t the dancer’s fault – they reflect inadequacies in ballet pedagogy. Young artists often are not getting what they need to succeed. And it’s nobody’s fault really.

But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do all we can to fix it.

How to Build Technique That Enables Artistry

Ballet class and ballet school exist for a reason—no one, not even the most naturally gifted dancer, can skip the work. Quick fixes don’t work. Cross-training, pilates, yoga, and random gym routines do not replace day-in, day-out ballet class under skilled teachers. “Muscle memory” from correct repetition at the barre and in center is what shapes the ballet dancer’s instrument.

Modern dance, jazz, and other art forms may allow you more leeway – but classical ballet is built on decades of technical development. Technique is the passport to creative power for every professional ballet dancer.

The path to technical mastery that enables artistic freedom requires:

- Starting with fundamentals: No matter your current level, revisit the fundamentals of turnout and placement regularly. These aren’t “beginner” concepts but the perpetual foundation of all ballet technique.

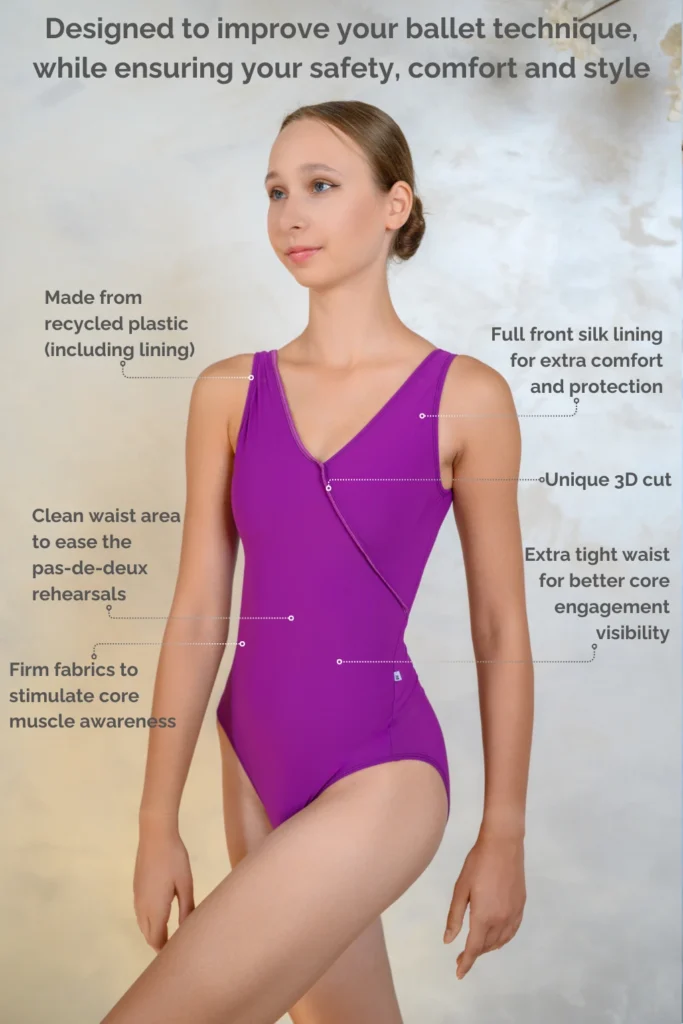

- Prioritizing strength development: Focus on building the specific strength patterns needed for ballet, particularly in the core and hip rotators. Our leotards at ArtCasse are specifically designed to help dancers develop proper muscular engagement.

- Valuing precision over quantity: Rather than mindlessly repeating exercises, approach each movement with full attention to detail. One perfectly executed tendu teaches your body more than dozens of careless repetitions.

- Understanding the purpose of each exercise: Each element of ballet class exists for a specific purpose in developing technique. When you understand why you’re doing something, you can execute it more effectively.

If you’re struggling with any of these elements, our “7 Quick Ballet Posture Fixes” checklist provides targeted solutions for common placement issues.

The Final Stage: When Technique Becomes Intuitive

The ultimate goal is to reach a state where technique becomes intuitive – where your body simply knows what to do without conscious monitoring. This is when artistry truly flourishes.

When your technique becomes intuitive, your body becomes both the instrument and the artist in one. This unique characteristic of ballet distinguishes it from other art forms. The ballet dancer simultaneously creates and embodies the art.

At this level, the dancer can express emotions beyond what words can capture. They can communicate the most profound human experiences purely through movement. This is ballet’s highest purpose – to express feelings that reach beyond the limits of language.

Conclusion: Technique as Liberation, Not Limitation

The notion that ballet technique limits artistic expression fundamentally misunderstands the relationship between the two. Technique isn’t the opponent of artistry – it’s the pathway to it.

When dancers embrace this understanding, they stop seeing technique as a set of restrictive rules and begin recognizing it as the very thing that will free them to express themselves fully.

By building technical mastery from the ground up, focusing on turnout, placement, and stability, dancers create the conditions for their artistry to flourish without limitations. Only then can they become true ballet artists, capable of moving audiences through the unique expressive power of classical ballet.

![[P] [ST] ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-AmethystPurple-Front2 [JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse - La Première Coupe - Amethyst Purple - Front](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-AmethystPurple-Front2-800x800.jpg)

![[P] [ST] ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-IndigoBlue-Front [JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse - La Première Coupe - Indigo Blue - Front](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-IndigoBlue-Front-800x800.jpg)

![[P] [ST] ArtCasse Premium Quality Ballet Leotards – La Premiere Coupe – Steel Blue – Front [JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse Premium Quality Ballet Leotards - La Première Coupe - Steel Blue - Front](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-SteelBlue-Front-800x800.jpg)

![[JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse Premium Quality Ballet Leotards - La Première Coupe - Steel Blue - Front](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-SteelBlue-Front-681x1024.jpg)

![[JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse - La Première Coupe - Steel Blue - Back](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-SteelBlue-Back1-681x1024.jpg)

![[JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse - La Première Coupe - Steel Blue - Side](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-SteelBlue-Side-681x1024.jpg)

![[JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse - La Première Coupe - Amethyst Purple - Detail](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-AmethystPurple-Detail-681x1024.jpg)

![[JPG REQUIRED FOR FACEBOOK] ArtCasse - La Première Coupe - Indigo Blue - Detail](https://www.artcasse.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/P-ST-ArtCasse-LaPremiereCoupe-IndigoBlue-Detail-681x1024.jpg)